The Binary Wall

There’s a dangerous phase in every ambitious project. It comes right after you’ve slain a few dragons and the path ahead looks clear. Your core abstractions feel sound, your tests are green, and for the first time in a long time, you’re not fighting the code, you’re dancing with it. You get confident. You get comfortable. You start to believe your own hype.

We were deep in that phase. Our new graph-aware database had just elegantly solved the circular reference problem that had nearly melted our CPUs. The framework felt solid, stable, and surprisingly complete. The nightly calls, once filled with frantic debugging and existential dread, had become calm, productive sessions where we were actually building things with our own tool. The feeling was intoxicating.

To celebrate, we started building a proper internal dashboard—the kind of tool we’d always wanted but never had the time to build. It needed user profiles, and user profiles needed avatars. "Let's add a profile picture upload," one of us said, with the casual air of someone suggesting adding a new button style. It was a five-minute task, tops. A footnote.

That footnote would become a two-week siege. That simple button would lead us to the brink of abandoning our entire philosophy. We were about to run head-first, at full speed, into the Binary Wall.

The first sign of trouble was an ugly TypeError: an object could not be cloned. Someone had wired up a file input, grabbed the File object from the event, and passed it into our beautiful server() function, expecting it to just work. The server didn't just reject it; it acted as if we’d fed it nonsense.

The problem, of course, is that our whole universe was built on a simple, elegant lie. The lie is that the client and server share the same memory. They don't. We just faked it with a clever system that serializes data and closures into JSON, sends them across the wire, and reassembles them. It’s a magnificent illusion, but it only works for things that can be expressed as text. A File object is not text. It's a blob of raw bytes. It's a fundamentally different kind of matter. We had built a hyper-efficient pneumatic tube system for sending letters, and we were now trying to mail a bowling ball.

The mood on the call that night was grim. The beautiful, seamless bridge we’d built between the client and server had a giant, file-shaped hole in it.

Our first attempt to fix it was born of pure desperation: the Base64 Heresy. "What if," someone whispered, "we just read the file on the client, encode it as a Base64 string, and pass that to the server() function?" It was a dirty, disgusting hack, and we all knew it. But it might just work. We tried it. The browser tab locked up for ten seconds as it tried to encode a 5MB image into a colossal string. The resulting JSON payload was 33% larger than the original file. The server’s memory usage spiked as it decoded the string. It worked, in the same way that using a sledgehammer to crack a nut works. It was brutal, inefficient, and an insult to everything we had built. We erased it from the whiteboard with a sense of shame.

This led to the Great Compromise Debate. The pragmatist on our team, voice heavy with resignation, made the sensible suggestion. "Look, let's just be adults about this. We’ll create one, single, special REST endpoint: POST /api/upload. We'll use multipart/form-data like the rest of the planet. It’s a special case for a special type of data."

The room went quiet. He was right, of course. It was the obvious, battle-tested solution. It was also a total betrayal. It meant that 99% of our application would be built with this magical, zero-API framework, but for this one common feature, developers would have to step out of our world and into a messy legacy of manual fetch calls, headers, and response handling. It would break the spell. It would create a second-class citizen for data transfer. Today it's a file upload endpoint. Tomorrow it’s a special endpoint for streaming logs. Before you know it, you’re just rebuilding Express.js, one compromise at a time. We were on the verge of giving up, of admitting that the "accidental complexity" we had declared war on was actually necessary complexity.

The breakthrough came late one night, fueled by stale coffee and existential angst. We were staring at the problem, stuck in the same loop. "We can't get the file into the server() function."

Then, the shift in perspective. "What if we stop trying to put the file in the function? What if the function could just... reach out and grab it?"

The idea was to treat the File object not as data, but as a pointer. When our engine prepares the server() closure to send across the wire, it sees the File object. Instead of trying to read it, it replaces it with a unique ID token. It then whispers to a separate part of the client-side runtime, "Hey, you see that file? Start streaming it to the server and tag it with this ID. Don't block, just go."

On the server, when the server() function executes, it sees the token. It doesn't have the file yet, but it knows it's coming. The variable that the developer thinks is a File object is actually a special server-side proxy—a "promise" of a file—that knows how to wait for the stream associated with its ID.

This was it. This was the way. We weren't breaking our abstraction; we were teaching it a new language. The code that followed was a frantic, joyous blur. And the result was better than we could have imagined. We could keep our perfect, beautiful syntax. The upload logic could live right inside the click handler. And as a side effect, we solved the single most annoying part of file uploads for free.

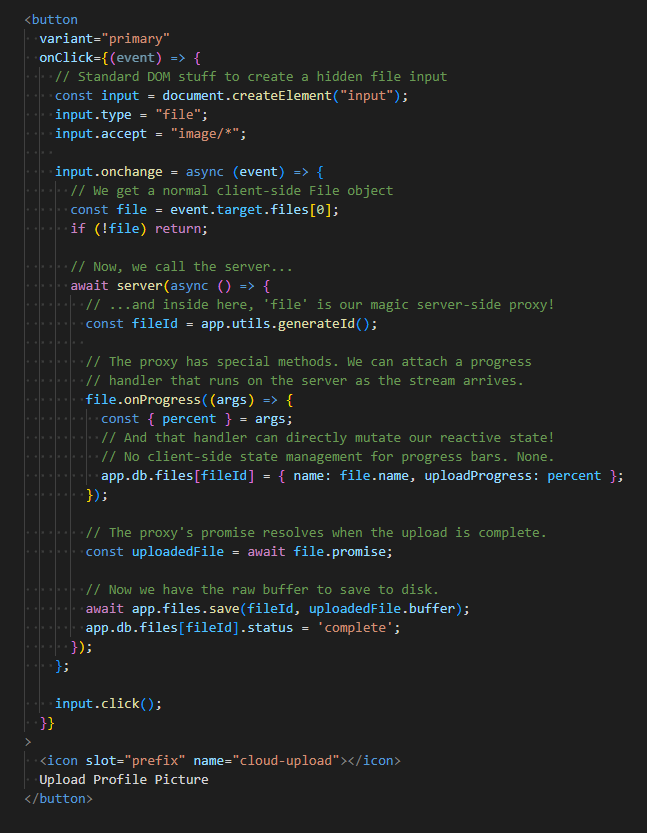

Here is the final code. It is a trophy earned through a fortnight of pure pain.

Look at that file.onProgress block. In any other framework, that logic is a nightmare. You need a client-side state variable for progress, another for the file name, another for the loading state, and you have to orchestrate updates from an XMLHttpRequest event listener. Here? You just modify a database object on the server. The rest of our reactive engine handles updating the UI automatically. It just works.

We had stared into the abyss of compromise and refused to blink. We hit the Binary Wall, and instead of turning back, we found a way to phase through it. This victory was about more than just a feature; it was a validation of our entire philosophy. The real world is messy, but with the right abstractions, the developer’s world doesn’t have to be.