Separation of Concerns is a Lie

For the last few weeks, a new kind of quiet has settled over our late-night calls. The frantic energy of chasing down fundamental breakthroughs—the binary protocol, the file-backed state, the magic of the server() function—has been replaced by a calmer, more focused rhythm. We've been building things. Small, internal apps. Complex components. We've been pushing our own creation to see where it shines and where it breaks.

This stability has given us the headspace to think less about the _what_ and more about the _how_. Not "what can this tech do?" but "what does it feel like to build with this tech?" And as we used our own tools, a conviction began to form, an idea that felt so contrary to decades of established best practices that we were almost afraid to say it out loud.

We've been taught our entire careers that "Separation of Concerns" is a cardinal virtue of software engineering. The principle is simple: keep your presentation (HTML), your styling (CSS), your client-side logic (JavaScript), and your server-side logic (the API) in separate files, separate modules, separate domains.

We've come to believe it's a lie.

Or, to be more precise, it's a solution to a problem that no longer needs to exist. It's a pattern that forces us to separate things that are, in reality, intrinsically linked. Think about a simple "Add to Cart" button. To understand that single feature in a conventional modern web application, a developer must embark on a scavenger hunt across five different files and contexts. The code isn't separated by _concern_; it's been shattered into tiny, disconnected pieces.

Our "aha" moment came when we realized that the server() function we built wasn't just a clever technical trick; it was a philosophical statement. It allowed the server-side logic to live, literally, inside the client-side event handler. This led us to a new principle, one that we wrote down in an internal document that has since become our constitution: **Locality of Behavior**.

The principle is this: all the code that makes a piece of the UI function—the structure that creates it, the event that brings it to life, and the logic that it executes—should live in the same place.

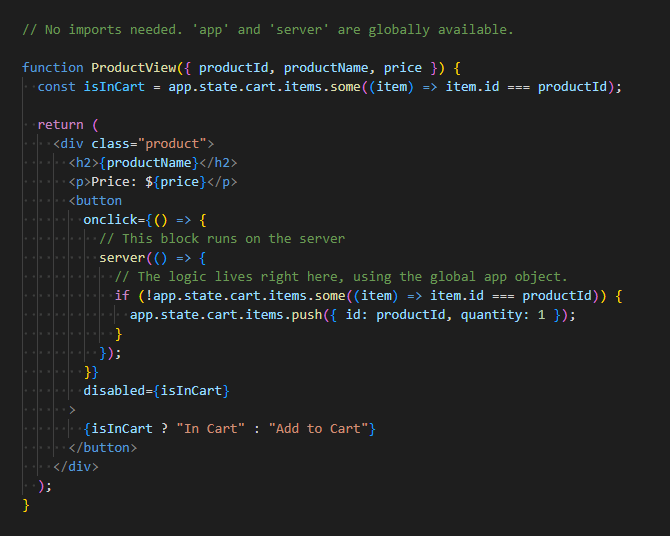

Here is that "Add to Cart" button, the zero.ts way:

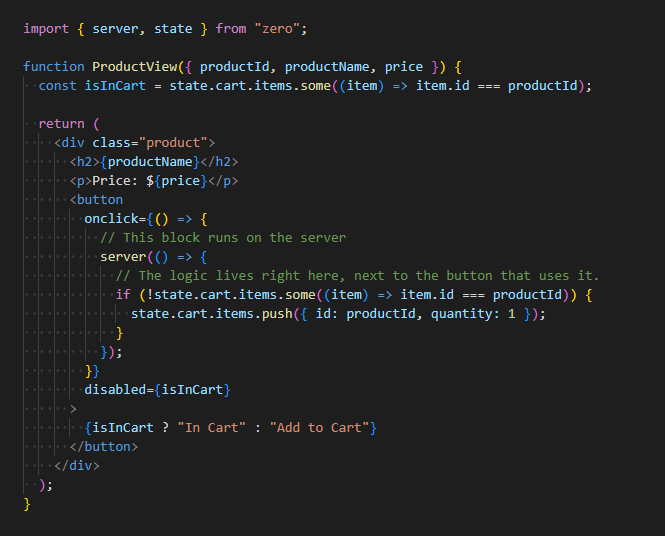

This felt like a massive leap forward. But as we lived with this new pattern, we noticed another, more subtle point of friction. A tiny papercut that appeared at the top of every file: import { server, state } from "zero";.

It's a single line of boilerplate. But it's a ghost of the old way of thinking, a constant reminder of boundaries and modules. It led to another, more profound, late-night conversation. "Why are we importing state?" one of us asked. "The entire application needs access to the state. Why are we forcing the developer to declare their intent to use it in every single file? Why do we create these artificial boundaries and contexts to pass it around?"

The question was liberating. What if state was just... there? Everywhere. Always. The same went for server(). It's a fundamental capability of the environment we're creating. Why should it be imported? What if it was just a global utility, always available?

This led to an epiphany. We could eliminate this final piece of boilerplate by providing a single, globally available app object to hold our state, and making server a true global. The shared state would live on app.state. It would be available in every file, on both the client and the server, without an import statement.

The code is now completely self-contained, taken to its logical conclusion: